There has been a

Russian Orthodox religious presence on Mont Athos for a thousand years, of

which the great monastery of St Panteleimon was and remains the centre. But in

the nineteenth century, especially from the 1840s onwards, successive Tsarist

governments supported financially and diplomatically the creation and expansion

of newer institutions, technically inferior to monasteries but in practice

coming to exceed in the size of their estates and the number of monks they

housed the old ruling monasteries. Three institutions stand out: the Skete [ monastic community] of the Prophet Elijah (Ilinski Sikt), a dependency of the Greek Orthodox monastery of

Pantokrator but housing first Ukrainian and then Russian monks; the Kellion [cell] of St John Chrysostomom (Ioanna Zlatousta), a dependency of the Serbian Orthodox monastery

of Hilandar; and the Skete of St Andrew

(Andreeveski Sikt and sometimes

called Serail), a dependency of the

Greek Orthodox monastery of Vatopedi.

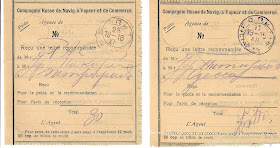

Until 1912, Mont Athos

was part of the Ottoman Empire with a Turkish governor in residence and Ottoman

customs, immigration and postal agencies located in the port of Daphne and the

small administrative town of Karyes. In addition, and as elsewhere in the Levant,

the Russian company ROPiT maintained a shipping agency and a post office on

Athos with significant autonomy from Turkish control. For example, mail from

Russia could travel by ROPiT ship from Odessa direct to Athos and be distributed

to the Russian communities by Russian postal officials. But Russian mail could

also be transferred to the Ottoman system in Constantinople for onward

transmission, and some was.

Spiritual authority over the monasteries rested (and

still rests) with the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. When secular

authority over Athos passed to Greece in 1912, the spiritual arrangements

remained unchanged.

From 1912 on, the

Russian Orthodox communities suffered a succession of blows from which they did

not recover.

First, in 1913 the Imperial Russian government

responded to perceived heretical tendencies among the monastic communities by

sending in gunboats and troops and, after violet clashes, forcibly deporting

about eight hundred monks who were returned to Russia, tried, defrocked and

internally exiled. The number of monks was thereby reduced by somewhere between

a third and a half.

Second, the First World

War led to a reduction in contacts and financing from Russia.

Third, the

Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 cut the remaining contacts almost to nil.

The Russian communities

went into long term decline and by the 1960s the few remaining elderly monks

were completely unable to maintain the vast properties which they occupied. The

significant library of the Andreevski Skete was destroyed by fire in 1958; the

last monk there died in 1971 and the

Andreevski estate reverted to the Greek monastery of Vatopedi. Even though it

was re-occupied by Greek monks in the 1990s, modern photographs show the

skete’s original pharmacy, candle factory and photographic studio untouched

except by the mice and the weather.

As

recently as 2017, online photographs of the Kellion of St John show a ruined

building with administrative offices from which furniture has been removed but

where the paperwork has been left in heaps to rot on the floors.

At some point in the

1970s, in an attempt to raise funds, monks on Mont Athos packed up old and

unwanted administrative papers into suitcases and travelled to Thessaloniki and

elsewhere attempting to sell them to collectors and dealers. They had only

limited success and most of the old paperwork was left to rot (as shown by the

St John photographs already mentioned) or was used for fire lighting in

communities which still had no access to electricity.

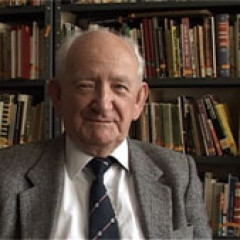

Just one collector

appears to have taken a serious interest in what the monks were offering, the

late Stavros Christou, and it is his collection of Athos-related material which

is offered in this sale. The collection includes material from many other sources,

but at its core is what was offered to Mr Christou in the 1970s. It is

dominated by material from the period 1840s - 1913 which was the hey-day of Russian

monasticism on Mont Athos when ships arrived almost daily, mail came in

sackfuls, and goods needed by the monastic communities arrived not only from

Odessa but from suppliers across Russia.